Introduction to LDP

Linked Data Platform (LDP) is a W3C recommendation that defines a set of rules to provide an architecture for read-write Linked Data on the web. This blog post is an introduction to the concept of Linked Data and how to get started with the Linked Data Platform.

What is Linked Data anyway?

If we are going to talk about the Linked Data Platform we should start by talking about Linked Data (if you are familiar with Linked Data already feel free to skip this section.)

Linked Data is a concept that Tim Bernes-Lee defined in 2006 in which he articulated a vision to allow the World Wide Web to move from being about linking documents (i.e. HTML web pages) that humans can read and navigate to a new model, know as the Semantic Web, that will include documents and data that both humans and machines can process. In his own words:

The Semantic Web isn't just about putting data on the web.

It is about making links, so that a person or machine can explore the web of data.

With linked data, when you have some of it, you can find other, related, data.

In the same paper Tim Bernes-Lee suggested four simple rules to help materialize this vision.

- Use URIs as names for

- Use HTTP URIs so that people can look up those names

- When someone looks up a URI, provide useful information, using the standards (RDF, SPARQL)

- Include links to other URIs so that they can discover more things

Over time people started making their data available following these rules and because people were using well-known standard technologies the exchange of data was easier to automate (compared for example to parsing HTML pages to follow links.)

The semantic web uses something called Resource Description Framework (RDF) to represent data. RDF is a way of modeling data using a three part statement that consist of a subject, a predicate, and an object. For example to indicate the title of a book we might have a statement as follows:

<book123> <title> "A Brief History of Time"

If you are new to RDF but are familiar with relational databases take a look at RDF for Relational Database Heads for a quick comparison between the two. Chapter 3 on the Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist has a great explanation of RDF and why it is important.

Now, let's say that we have the URL for a resource http://dbpedia.org/resource/Abraham_Lincoln and we query DBpedia, a well known provider of Linked Data, for this resource. The result of this query we might be something as follows:

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Abraham_Lincoln> <rdf:type> <http://dbpedia.org/class/yago/PresidentsOfTheUnitedStates> . <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Abraham_Lincoln> <dbp:birthPlaceName> "Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S." . <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Abraham_Lincoln> <dbo:birthPlace> <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Hodgenville,_Kentucky> .

By glancing at this data we can conclude that Abraham Lincoln was a president of the United States that was born in Hodgeville, KY. The interesting part about Linked Data comes when we follow some of the links provided in the data, for example, http://dbpedia.org/resource/Hodgenville,_Kentucky. If we query DBpedia for this resource we might get a result set as follows:

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Hodgenville,_Kentucky> <dbo:populationTotal> "3206" . <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Hodgenville,_Kentucky> <dbo:thumbnail> <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Special:FilePath/Hodgenville_KY_Town_Square.jpg?width=300> . <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Hodgenville,_Kentucky> <dbo:isPartOf> <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Kentucky> .

This rudimentary example shows the power of Linked Data. By following the links that we got in first result set for Abraham Lincoln we are able to find more information about our original query. In this case we were also able to figure out that the town where Lincoln was born has a population of 3206 people and we even got a thumbnail image of the town, notice that this thumbnail is not even hosted at DBPedia.

People have done amazing things with Linked Data. For example DBpedia "a crowd-sourced community effort to extract structured information from Wikipedia" allows you to download and query Wikipedia information as Linked Data. Their about page has the following statistics:

The English version of the DBpedia knowledge base describes 4.58 million things, out of which 4.22 million are classified in a consistent ontology, including 1,445,000 persons, 735,000 places (including 478,000 populated places), 411,000 creative works (including 123,000 music albums, 87,000 films and 19,000 video games), 241,000 organizations (including 58,000 companies and 49,000 educational institutions), 251,000 species and 6,000 diseases.

In 2009 Tim Bernes-Lee gave a TED Talk titled the year open data went worldwide in which he showed real examples of Linked Data used in the wild and at large scale.

The Linked Jazz project is another example of using Linked Data to create amazing visualization of data. Christina Harlow has a blog post in which she explains how libraries are leveraging Linked Data.

Tim Bernes-Lee vision kicked off the Linked Data movement in 2006 and it served us well. But his original vision only covered how to provide Linked Data for others to consume (i.e. to read and follow) and failed short of describing for a mechanism to allow others to add new data and update existing data. In his WWW2014 presentation Arnauld J Le Hors described how, before the Linked Data Platform was conceived, there was no formal definition for using Linked Data for application integration. In his words:

State of the art was about publishing read-only data on the web and updated as large dumps or via SPARQL entry point. Tim Berners-Lee four principles are a terrific foundation but don't go far enough. Many unanswered questions: How do I create a resource? It seems obvious that you use POST to create, what do you POST to? Where can I get a list of resources that already exist? Which vocabulary do I use? Which media types do I use?

Linked Data Platform

Linked Data Platform (LDP) is a recommendation by the W3C to formalize how read-write should be performed on Linked Data over the web. This is how the W3C defines LDP:

Linked Data Platform (LDP) defines a set of rules for HTTP operations on web resources, some based on RDF, to provide an architecture for read-write Linked Data on the web.

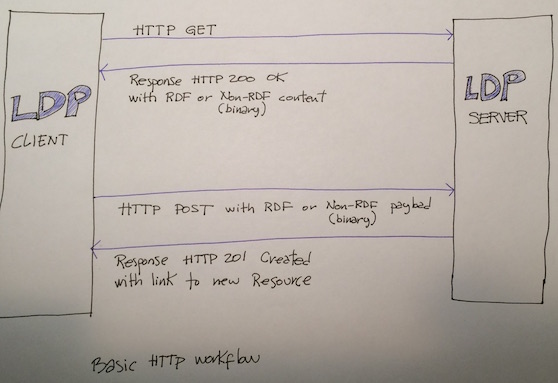

In other words, LDP is the definition on how to provide an HTTP API to allow applications to read and write Linked Data. This means that if you have an LDP Server and a LDP Client they can communicate to each other using the rules defined in the recommendation to retrieve, create, delete, and update data. The LDP recommendation defines clear rules on what HTTP verbs should be used to fetch data, how servers should indicate the operations allowed on the resources that they expose, how to create new resources, and how to update the existing ones.

In practice this looks more or less like this:

LDP Concepts

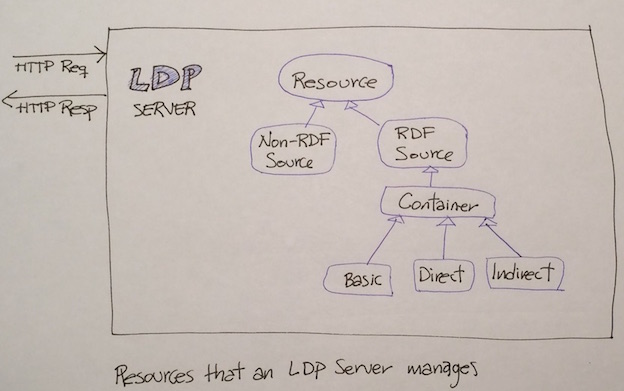

LDP defines several concepts that are important to understand before diving into the details. Everything in LDP is a Resource. This includes sources that are expressed in RDF (RDF Sources) like the triples that we saw in the previous example with Abraham Lincoln's data and also Non-RDF Sources which includes HTML web pages, PDF documents, image/audio/video files, binaries, and everything else.

A big part of LDP is dedicated to managing resources contained within another resource (i.e. containers). As Robert Sanderson indicated "containers are at the heart of LDP". In LDP there are three kinds of containers (basic, direct, and indirect) and they are all RDF Sources themselves. The fact that containers are RDF Sources means that they are described with RDF triples.

The following picture shows how these resources are structured:

LDP in Action

In the next sections we will see a few examples on how to use LDP to read and write data. These examples will show HTTP requests (including verbs, URLs, headers, and payload) that must be issued by a client and the <em>HTTP responses</em> (including headers and body) that a LDP Server will return. The examples in this post will assume that the LDP Server is hosting information about a blog with blog entries, comments, and attachments to demonstrate how to work with RDF and Non-RDF Sources.

If you have an LDP Server available you can execute these requests through any program capable of issuing HTTP requests including cURL. If you don't have an LDP Server available checkout the section LDP Servers Implementation later in this post for a few samples that you can download and play with.

Reading Data

To fetch an LDP resource a client just needs to issue a basic HTTP request as follows:

GET /blog123 Host: www.somewhere.org

Assuming we have an LDP Server at www.somewhere.org with information about resource blog123 the server will return a response as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Type: text/turtle Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#BasicContainer>; rel="type", <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Resource>; rel="type" @prefix dcterms: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/>. @prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog123/> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#RDFSource> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog123/> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Container> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog123/> <dc:title> "This is the blog for user 123" . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog123/> <dc:subjects> "Weekly posts about technology and stuff" .

A few things to notice in the response from the LDP Server:

- By default the result is returned in Turtle. Clients can request other formats including JSON-LD or RDF-XML.

- The server is indicating (via the HTTP header Link) that this is a Basic Container. From the diagrams in the previous section we know this is a kind of RDF Source. This means that we expect to see triples in the body of the response.

- In this example I am using

<rdf:type>as the predicate in the triples. Servers typically abbreviate this asaas per the Turtle specification.

Creating New Resources

LDP is all about making Linked Data read-write so let's jump right into an example on how to

create a new resource in our fictitious blog. To create a new resource we use HTTP POST as follows:

POST / Host: www.somewhere.org

If the LDP Server creates the new resource we would get a response as this:

HTTP/1.1 201 Created Location: http://www.somewhere.org/abc123xyz Content-Type: text/plain

Notice that the server returns an HTTP 201 status code (created) and the location of the new resource created (http://www.somewhere.org/abc123xyz) The LDP recommendations indicates that if the client does not request a specific ID for the new resource the server automatically generates one (abc123xyz in our example.) Clients may request a specific ID for the new resource via the Slug HTTP header. For example if the request would have been:

POST / Host: www.somewhere.org Slug: blog789

The server might have returned:

HTTP/1.1 201 Created Location: http://www.somewhere.org/blog789 Content-Type: text/plain

We can also indicate in the body of the request the triples that we want in the new resource for example we could have issued a request like this:

POST / Host: www.somewhere.org Slug: blog789 <> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title> "title of the blog for user 789" . <> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/subject> "random topics" .

Again, assuming the resource was created successfully we could fetch it via HTTP GET

GET /blog789 Host: www.somewhere.org

and get a response as follows with the triples that we indicated (title and subject) plus a few triples that the LDP Server automatically adds to the new resource. The triples added by the LDP Server are called "served-managed triples" and are readonly.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Type: text/turtle Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#BasicContainer>; rel="type", <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Resource>; rel="type" @prefix dcterms: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/>. @prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#RDFSource> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Container> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <dc:title> "title of the blog for user 789" . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <dc:subject> "random topics" .

Adding Resources to a Container

When we fetched the new blog789 resource the LDP Server indicated that the resource was an RDF Source (in one of the triples) and that it was a Basic Container (in the Link HTTP header). An LDP Basic Container allows us to add new elements to it also via HTTP POST. For example we could issue a new HTTP POST as follow:

POST /blog789 Host: www.somewhere.org Slug: entry1 <> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title> "title of my first blog post" <> <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/subject> "social sciences" .

assuming the server creates the new resource we could now fetch it via an HTTP GET /blog789/entry1 and get a response as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Type: text/turtle Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#BasicContainer>; rel="type", <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Resource>; rel="type" <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/entry1> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#RDFSource> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/entry1> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Container> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/entry1> <dc:title> "title of my first blog post" . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/entry1> <dc:subject> "social sciences" .

Because we issued a POST to a Basic Container the LDP Server also updates the container itself to make it aware of the new resource that it now contains. If we fetch the container via HTTP GET blog789/ we would get a response as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Type: text/turtle Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#BasicContainer>; rel="type", <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Resource>; rel="type" @prefix dcterms: <http://purl.org/dc/terms/>. @prefix ldp: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#> . @prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#RDFSource> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <rdf:type> <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Container> . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <dc:title> "title of the blog for user 789" . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <dc:subject> "random topics" . <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/> <ldp:contains> <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/entry1> .

Notice the last triple in this response. It has a predicate <ldp:contains> and it points to the newly added resource <http://www.somewhere.org/blog789/entry1>. This is an example of the "rules for HTTP operations on web resources, some based on RDF, to provide an architecture for read-write Linked Data on the web" that the W3C recommendation alludes on its home page.

This might looks like a simple thing, and in a way it is. However, the power of this simple architecture is that it provides a common mechanism to handle read-write Linked Data so that we don't come up with custom implementations on each application that then everybody needs to write custom code in order to participate.

When we delete a resource that is inside a container, for example HTTP DELETE /blog789/entry1 the server will delete the specified resource and, per the LDP recommendation, automatically remove the reference indicated in the <ldp:contains> in the container.

There are two other types of containers in LDP, namely Direct Container and Indirect Container that provide different options to handle this automatic linking between a container and the resources that it contains. The LDP recommendation goes into great detail on how they each differ and you might want to check it out. This presentation by Nandana Mihindukulasooriya also gives good example on how to use them. I have also written LDP Containers for the Perplexed to elaborate on the differences between these containers.

One last thing on HTTP POST

In the previous examples every time we issued an HTTP POST we did it against an LDP Container and the result was that a new resource was created inside the container.

If we issue an HTTP POST to a Non-RDF Source the server will refuse the request since it is not possible (under the LDP rules) to create a resource inside a Non-RDF Source.

It is not clear to me what would happen if we issue an HTTP to an RDF Source that is not a container. I would expect the server to refuse the request but the W3C recommendation is not explicit on this. The recommendation says that containers can accept POST but does not say anything about RDF Sources that are not containers.

What about Non-RDF data?

So far we have seen examples on how to fetch, create, and delete RDF Sources from an LDP Server. But not all the data that we deal with is in RDF. Most APIs need to access and account for resources that are in other formats. The LDP recommendation has specific provisions to handle these kind of resources.

Let's say that we want to add a thumbnail to each of the blogs that we have in our sample with the picture of each of the authors.

We could issue an HTTP requests as follows to add the image itself (a Non-RDF Source) to an LDP Server:

POST /

Host: www.somewhere.org

Slug: author789

Content-Type: image/jpeg

Content- Length: 1020

{the binary of the image goes here}

A couple of things to notice about this HTTP request:

- We are indicating via the Content-Type header that this is an image/jpeg

- We are passing the binary of the image (not RDF triples) in the body of the request

If you were to issue this request via cURL it would look like this:

curl -X POST --header "Slug: author789" --header "Content-Type: image/jpeg" --header "Content- Length: 1020" --data-binary "@author789.jpg" http://www.somewhere.org/

Now that the Non-RDF Source has been created we could easily fetch via a HTTP GET /author789 and we get back the binary data of the JPEG. If we don't want to fetch the binary data but just some information about it we could

issue an HTTP HEAD instead and the LDP Server will report something like this:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Length: 23151 Accept-Ranges: bytes Content-Disposition: attachment; filename="author789.jpg"; size=23151 Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#Resource>;rel="type" Link: <http://www.w3.org/ns/ldp#NonRDFSource>;rel="type" Allow: DELETE,HEAD,GET,PUT,OPTIONS Content-Type: image/jpeg

Notice how the Link header in the response clearly indicates that this is a Non-RDF Source. It is up to the LDP Client to handle the image appropriately.

So far we have added a new Non-RDF Source to the LDP Server and we can fetch, but we haven't updated the RDF Source for blog789 to point to it. We'll do that in the next section.

What About Updating Resources?

The LDP recommendation provides clear indications on how to use HTTP PUT to overwrite resources. You can issue an HTTP PUT to an existing resource and pass the data (RDF or Non-RDF) that you want to save and the resource will be replaced with the new data. The recommendation has provisions on how to handle conflics (via ETags) in case more than one client tries to replace the same resource and how to handle the case in which a client might try to update triples handled by the server.

However, the LDP recommendation does not provide a clear specification on how to update a subset of the triples in an RDF Source, say for example that you want to update the blog789 to include a new triple to point to the new author123 Non-RDF Source that we added but we want to leave everything else on blog789 unchanged.

There is something called Linked Data Patch (LD Patch) to handle this need that is in the works but this is not an official recommendation yet. The LD Patch home page states that the "Linked Data Platform Working Group is currently favoring LD Patch" but still has not decided. They allude to other candidate technologies to handle updates including "SPARQL 1.1, SparqlPatch, TurtlePatch, and RDF Patch".

Fedora 4, the LDP Server that I am most familiar with, uses SPARQL for updates. With SPARQL is possible to issue something like this to update an RDF Source:

PATCH /blog789

Host: www.somewhere.org

Content-Type: application/sparql-update

DELETE { }

INSERT {

<> <http://dbpedia.org/ontology/thumbnail> <http://www.somewhere.org/author789> .

}

WHERE { }

LDP Server Implementations

The W3C has a list of different LDP implementations that are available for people to use. Check it out to find out which one is more appropriate for you.

I have been using Fedora 4 and a lot of the examples that I showed in this post were tested on it. Fedora is the repository of choice in Project Hydra, the stack that I am currently using.

Shameless plug. As a toy project I have implemented an LDP Server in Go and you can use it to play with LDP if you want a very simple server. Notice that this server is not compliant with the W3C recommendation and it's purely an experiment. However, my implementation is rather easy to install, just download the executable that is appropriate for your environment (Linux, Mac, Windows), run it, and start submitting cURL requests to it as described in the home page.

Parting Thoughts

On the book Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist the authors state that

the challenge for the design of the Semantic Web is not to make a web

infrastructure that is as smart as possible; it is to make an infrastructure

that is most appropriate to the job of integrating information on the Web

I think the Linked Data Platform is great step towards providing this kind of infrastructure. LDP does not make data or applications smart but it allows a new level of integration for creating and updating Linked Data that was missing.

I would be the first to admit that the LDP recommendation is a bit hard to follow at the beginning. One might be tempted to even discard it and implement a custom API for our own Linked Data, but that would be short sighted. If we all implement a different approach to read-write Linked Data pretty soon we are going to have to have different implementations for each data set that we interact with, a less than ideal situation.

I think this quote by Brian Sletten puts it rather nicely:

The LDP builds on the principles of REST, the web, and Linked Data but

provides more structure to harmonize behavior across compatible containers.

If tool vendors understand and support these standards consistently, the

ecosystem will be more likely to work together. Actual implementation

details are still largely irrelevant, provided the resource-oriented

behavior is supported

There is a ton of information on the W3C LDP main page that I am not covering on this blog post that is worth looking into if you are thinking about interfacing with an LDP Server or implement one to expose your own Linked Data. The LDP Primer also by the W3C is another good source of information.

I wrote this blog post as I prepared to give a presentation on Linked Data Platform at Hydra Connect in Minneapolis. The slides that I used for this presentation are available here in PDF or PowerPoint.