Simple Branching Strategies for Team Foundation Server

In this blog post I describe some branching strategies that I've found useful when using traditional source control systems like Team Foundation Server (TFS).

Team Foundation Server has very good branching and merging capabilities that can help teams manage source code in a team environment. However, despite the fact that TFS provides excellent branching and merging capabilities, I usually recommend a simple approach to branching since the process of branching and merging can easily get convoluted and out of control even with the best of tools.

The basic idea

The way I approach branching in TFS is to have one main branch for all on-going development on the project. This is the branch where developers do their work on a daily basis. Once the team reaches the point where the code will be released to production then a second branch (a release branch) is created. This release branch is a copy of the code that will be pushed to production. The main branch stays active and most of the team will continue working of the main branch as they add new features to be released in a future version of the system. A few of the developers will make changes to the release branch to fix bugs that must be ironed out before the release goes out or even after it has been promoted to production.

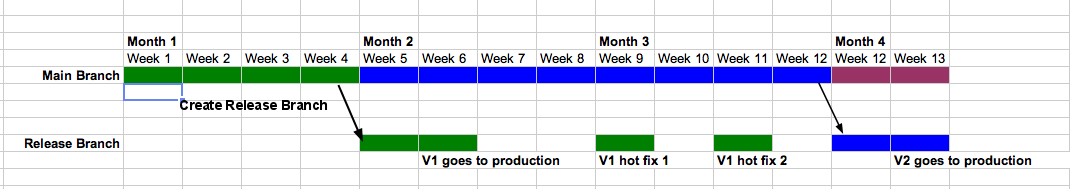

The following picture shows an example of these concepts and how the branches are used over time.

In the previous picture we can see how the team worked on the main branch from week 1 through week 4 (the green bars.) At the end of week 4 the team decided this code had all the features needed for a version 1.0 release and created a release branch with these features.

During the next two weeks the team made a few changes to the code in the release branch, perhaps fixed a few show-stopper bugs before promoting to production. Meanwhile, the rest of the team continued working on the main branch on long term features to be released in version 2.0 (the blue bars.)

The team worked from week 5 through week 12 on the main branch (the blue bars.) During this time there were two hot fixes pushed to production from the release branch (green bars on week 9 and week 11.) The nice thing about the release branch concept is that it gives us total isolation from the on-going long term development on the main branch. Since the release branch is an exact copy of what's in production updating this branch when a hot-fix is needed is very safe and easy.

On week 12, the team decided that they were ready to promote the next major version of the system to production. A that time the main branch was branched out again to the release branch. From this point the cycle is repeated: hot fixes for version 2 are made on the release branch while all new development for version 3.0 is done on the main development branch (now the purple bars.)

Variations to this approach

In some teams we have made a small variation to this pattern in which a totally new branch is created every time a new major version of the system is deployed to production. For example, we could create a totally new branch on week 12 for release 2 rather than sticking the version 2.0 code on the existing release branch. The advantage of this variation is that, if at the end of week 12 we need to do a hot fix to version 1 (while version 2 is still in QA) we can easily make the fix on the original release 1 branch since that branch is still an exact copy of what's in production. This could be a life saver and worth consideration.

I first read about the concepts of the main branch and a release branch in the book Software Configuration Management Patterns: Effective Teamwork, Practical Integration by Stephen P. Berczuk and Brad Appleton. This book is a good read if you want more details on the approach that I describe in this post. Chapter 4 and 5 describe the Mainline and Active Development Line patterns while chapter 17 talks about the Release Line.

Merging - the dark side of branching

Regardless of how neat your branching strategy might be the real issues are found in the merging process. For example, in the previous picture I didn't indicate how changes made on weeks 5 and 6 on the release branch will be merged back to the main branch. The same is true on weeks 9 and 11 when hot fixes were applied to the release branch. If these changes are also needed in the main branch somebody will need to go perform this process.

There is nothing inherent to the branching strategy that I describe in this blog post that makes the merge process easier. Depending on the nature of the changes merging can be a messy process. The best that you can do with merging is to implement a workflow in which merging conflicting changes is minimized. However, since inevitably you will have conflicting changes to merge I find Jennifer Donnelly's advise on the subject rather valuable: merging should happen frequently and within context, in other words, by the person who made the change and as soon as possible. On small teams this is usually easy to do and prevents the merging process from becoming a disaster.

In closing...

The ideas that I've described in this blog are neither new nor the only options for branching. However, I've found them very useful for small teams working with centralized source control systems like Team Foundation Server. The fact that these ideas are simple to implement allow development teams to gain the most of branching (i.e. code isolation) without having to have a dedicated staff in charge of source control and merging.

Although I suspect these ideas apply to most traditional client-server source control systems I have only apply them with TFS. I am not sure however how well they fit with a distributed source control system like Git.